A threat to humans for millennia

Mosquitoes have been a persistent enemy of humans for thousands of years. Our history of being troubled by this ancient foe can be traced back through Chinese documents as early as 2700 BC, from clay tablets in Western Asia from 2000 BC, and on Egyptian papyrus from 1570 BC.1,2 Currently, mosquitoes and other blood-sucking insects are responsible for over 700,000 deaths per year around the world. This is because they can transfer diseases like malaria, dengue and yellow fever to humans.3,4 Some historians have suggested that, in the entire history of the human race, mosquitoes may be responsible for killing around half the people who have ever lived.5,6

So, you may be wondering, what did we do to deserve this? Why can’t mosquitoes just leave us alone?

Well, mosquitoes (whose name comes from the Spanish for ‘little flies’) depend on standing water to hatch and raise their young. Throughout history, humans have always collected and stored water for their own needs, whether by keeping rainwater in barrels or for irrigating crop fields. Recently, scientists at Princeton University discovered that mosquitoes living in areas with long and intense dry seasons have adapted ways to seek out humans more effectively. Because wherever humans are living, water must be close by.7,8

Humans and mosquitoes were drawn together thousands of years ago because of their shared need for water; however, humans also provide something else mosquitoes desperately need to reproduce human blood. Female mosquitoes require the nutrients (mainly vitamins) found in blood to produce their eggs.9

So, how do mosquitoes know where we are?

Mosquitoes have an amazing ability to zero in on us from afar and head straight for our bare skin. To do this, they use a combination of olfactory (smell), visual, and thermal cues to locate our flesh:10

-

Female mosquitoes have special nerves that can detect carbon dioxide in the air. Because the air we exhale contains more carbon dioxide than normal air, this enables mosquitos to detect humans from a distance.1,11

-

As they get closer, mosquitoes are then able to smell the odors on our skin, allowing them to get within biting range. They do this using thousands of sensory nerves in their antennae, mouthparts, and structures between their antennae and mouthparts, called ‘maxillary palps’.1,11,12

-

Finally, once up close, they can use our body heat to find a suitable landing site.10

What happens when we get bitten?

There are thousands of species of mosquitoes, but a distinguishing feature amongst all of them is method they use to bite us. The female possesses a tube-like mouthpart, called a proboscis, which is perfectly adapted to pierce our skin and draw blood.9

While obtaining blood from a human, the female mosquito injects some of its own saliva into our skin. The saliva contains substances that prevent our blood from clotting, so that the proboscis does not become trapped in our skin. Upon detecting this injection of saliva, our immune system reacts by releasing histamine and cytokines, substances that cause the itching and hives associated with mosquito bites.9

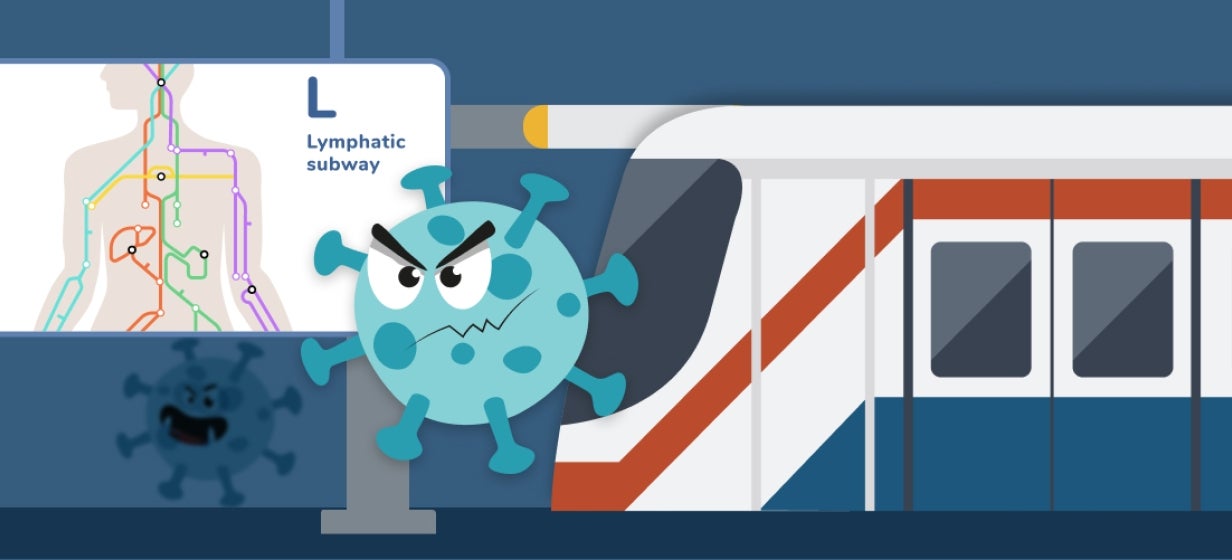

However, the potential danger is caused by what comes next: when a mosquito feeds on us, it also swallows any viruses or parasites living in the blood. These viruses and parasites can live inside the mosquito, and can be transferred to the next person the mosquito bites through its saliva. Any disease that is spread in this way from mosquito to human is known as a 'mosquito-borne disease'.13

While the mosquito may not be affected, these mosquito-borne diseases have caused immense suffering for humans throughout history, which are continuing in the present day. It is estimated that millions of people are infected each year with dengue and malaria, and hundreds of thousands more are affected by Zika, chikungunya and yellow fever.13 Dengue is the most rapidly spreading mosquito-borne viral disease in the world, and cases of dengue have increased over six folds since 2000.14

If you are worried about dengue or have a healthcare-related questions, please contact your doctor or other healthcare professional promptly.